Media empires rise and fall, but the explosive growth in popularity of websites such as BuzzFeed and Upworthy during the past several years ushered in a new phenomenon in content – the “curiosity gap.”

Mainstream media such as newspapers and magazines have long tantalized their audiences with salacious rumors and tawdry gossip to sell papers and ad inventory, but the emergence of clickbait and “snackable content” (perhaps one of the most loathsome terms in media) ignited an arms race to drive revenues and traffic by appealing to our innate sense of curiosity.

However, some experts have begun to speculate whether the curiosity gap is dead; some believe today’s media consumers have become desensitized to the constant barrage of amazement offered to us in our RSS feeds and on our smartphones, and that media outlets offering little more than rhetorical questions and cheap tricks are doomed to fail unless they try harder to earn their audience’s attention.

But are they right?

What Is the Curiosity Gap?

The curiosity gap is a theory and practice popularized by Upworthy and similar sites that leverage the reader’s curiosity to make them click through from an irresistible headline to the actual content. By creating a curiosity gap, you’re teasing your reader with a hint of what’s to come, without giving all the answers away. The curiosity gap can be used to compel people to click on a blog post they see on Twitter, an ad on Facebook, or a marketing email in their inbox.

There are three primary elements that go into the curiosity gap publishing model:

- Headlines

- Publishing frequency

- Virality

Let’s take a look at each.

The Curiosity Gap in Headlines

Arguably the most important element in the curiosity gap technique is the headline.

Upworthy is famed for its approach to headlines. The site requires all writers to devise at least 25 headlines per article, regardless of its length, topic, or angle.

This is a lot harder than it sounds.

Headlines have to be almost literally irresistible. They have to entice us in mere seconds (or less), and as such must balance information with intrigue; they have to tease just enough about the article to not only tempt us to click through, but also to give us enough information to decide whether the article is likely to be of interest to us in the first place.

Put another way, headlines have to be specific enough to entice the reader, but not so specific that the reader doesn’t need to click through.

As important as headlines are to the curiosity gap publishing model, they have rightfully attracted their fair share of detractors and criticism. This style of headline has also been accused of falling prey to diminishing returns – how long can audiences realistically be “amazed by what happened next”?

Whether they have become less effective or not, there is no disputing that headlines are a crucial element in the curiosity gap formula.

Publishing Frequency

Another common element in the curiosity gap publishing model is frequency.

Sites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy publish a lot of content, with dozens (or more) of posts being published every single day. There are several benefits of maintaining this kind of editorial calendar, the first of which is being able to publish content across a wide range of topics and subject areas to appeal to the huge audiences that these sites have.

Another benefit of publishing a lot of content is being able to mitigate the “losses” of poorer-performing content by simply publishing more; it becomes a numbers game when everything is a race to virality. The more content you publish, the more likely that one or more listicles will go viral.

Yet another upside to publishing a ton of content is that it provides the publisher with more raw data to work with in their A/B tests. Make no mistake – BuzzFeed and Upworthy didn’t become phenomenally popular by accident. This publishing model has allowed publishers to refine their approaches to headlines, content itself, and social promotion by analyzing ever-increasing volumes of data, which further drives the content machine.

Social Validation and Virality

The final piece of the puzzle is virality, or the likelihood that a piece of content will end up generating thousands (or even millions) of shares on social media.

Think about all the dumb quizzes you see your friends sharing on Facebook, for example. Many of them will be from sites such as BuzzFeed and Upworthy. This is because these publishers know (from looking at reams of data, as we covered a moment ago) that quizzes about which Harry Potter character you most closely identify with politically perform amazingly well in terms of social shares.

Virality is the endgame for publishers attempting to leverage the curiosity gap. The more widely content is shared on social, more traffic is directed to the site, engagement with the content is significantly higher, and – perhaps most importantly – the ad revenues are higher.

Is the Curiosity Gap Just Clickbait?

No – at least, that’s what publishers want you to believe.

Many prominent editors in publishing – including BuzzFeed’s Editor-in-Chief Ben Smith – claim their outlets do not publish clickbait. Yes, really.

Their argument hinges on the fact that clickbait is generally defined by the yawning chasm between the promise of the headline and the actual substance of the content. That’s why many publishers have veered away from the weary, sensationalist headlines we were all subjected to a couple of years ago; articles with the “one weird trick” to do something, or promises that “we won’t believe what happened next.”

Essentially, there’s one major difference between clickbait and content that attempts to leverage the curiosity gap, and that’s how the reader feels when they click through to the content.

Clickbait often leaves the reader dissatisfied, by either failing to deliver on the promise of the headline at all, or by purposefully deceiving the reader into clicking with little thought for what comes next. As we established earlier, successfully leveraging the curiosity gap requires social validation to promote successful content, something that isn’t possible if your reader is disgusted by your editorial trickery (more on this momentarily).

That said, there’s a very fine line between genuinely compelling content that pulls the right levers in our brains, and the sensationalist crap published by tabloids in a brazen attempt to get you to click through.

So, now we know a little more about what makes this publishing model unique, let’s take a look at some external factors that have contributed to changes in the media landscape.

Overall Trust in Media at Shocking New Lows

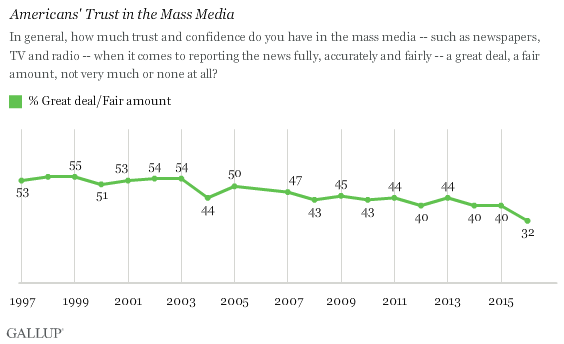

Recent data from Gallup indicates that consumer confidence in the media has sunk to unprecedented lows. Less than a third of respondents polled said they had “a great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in the media, with the largest drops in trust observed among younger and older demographics.

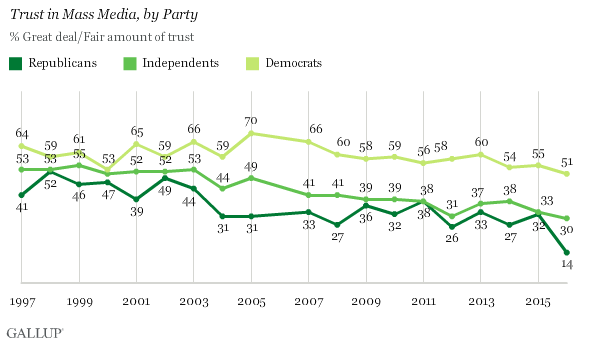

When you view this decline through the lens of political partisanship, it becomes even more dramatic. Gallup also compiled data for decreasing public trust in mass media by political affiliation, and last year alone, trust among Republican media consumers dropped from 32% in 2015 to just 14% last year:

What does this have to do with the curiosity gap? With consumer confidence in the media at its lowest level in recent memory, publishers have to tread very carefully when attempting to leverage the emotional triggers of their audience (more on this shortly).

Consumers are already leery of online content, and so trying to trick them is a particularly risky gambit – much more so now than it was even a couple of years ago.

How to Leverage the Curiosity Gap in Your Marketing

Trendy or not, the curiosity gap is a powerful technique that can really raise your click-through rates across channels from social media to your email campaigns. So, how can you – the small-business owner with a modest digital marketing operation – leverage the curiosity gap to drive traffic to your site? Here are six ways to use the curiosity gap to improve your marketing.

1. Leverage Emotional Triggers

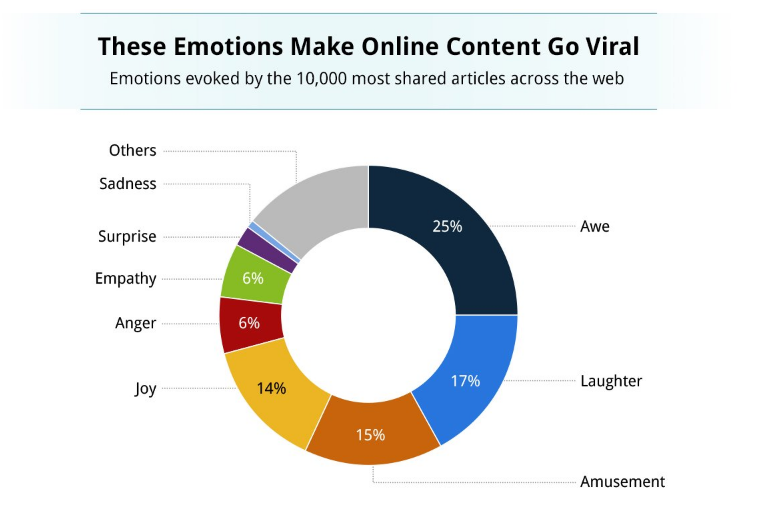

Much of the fake news we saw throughout the election here in the U.S. last year was so popular because it pandered to people’s emotions. Sure, most of this content was trash, but one thing it did extremely well was leverage emotional triggers.

Pushing people’s emotional buttons is one of the most effective techniques at your disposal when creating engaging content. Unfortunately, this process is as much art as it is science – not to mention extremely complicated. It’s also hugely dependent on the type of content you typically produce, your audience demographics, and numerous other factors.

It’s also important to bear in mind the kind of emotional responses you wish to elicit from your readers. Negative emotions such as anger may result in more social shares, but could also inadvertently harm your brand. Similarly, humor can be a highly effective tool in your content marketing, yet many B2B publishers shy away from trying to make their audience laugh for fear that such a tone isn’t appropriate.

Only you can determine whether appealing to a certain emotion in your content is suitable for your audience. That said, however you choose to do it, be sure your audience feels something after reading your content; there is no greater sin in content than to be bland and forgettable.

2. Respect Your Audience (and Its Intelligence)

You’ve probably sneered at a particularly egregious click bait headline or two in your time, so why would you resort to the same sleazy tactics to tempt your own audience into clicking through?

Clickbait relies primarily on deception to drive traffic. These publishers don’t care about dwell time, or scroll depth, or other engagement metrics – they just want the clicks and the pageviews to drive advertising revenue.

One of the best ways you can maintain your credibility as a publisher is by treating your readers with the respect they deserve. Sure, you can (and should) try to create intrigue in your content, but don’t resort to cheap trickery. If you wouldn’t click through a blatantly deceptive headline, don’t try to make your audience do it, either.

Delivering on the promise of your headline is crucial, especially when it comes to content. However, this principle also applies to other instances, such as ad or email headlines.

It doesn’t matter how compelling your testimonials are, or how attractive your emails are – if you fail to deliver on your subject lines, you will disappoint your audience. This could harm your conversion rates and even damage your brand, so tread carefully.

3. Focus on the Quality of Your Content

We know that readers crave quality content. We also know that social media platforms and Google’s search algorithm reward quality content with greater visibility. As such, you should focus on improving the quality of your content, rather than wasting time devising headlines that tempt readers to click through to mediocre articles.

That’s not to say you can’t create a sense of intrigue about your content, or that you shouldn’t try to leverage your audience’s curiosity at all. I am suggesting, however, that you try to focus on producing the very best content you possibly can. As tempting as it can be to resort to cheap trickery to increase traffic or other short-term benefits, focusing on publishing quality content consistently will yield far greater results in the long run.

As reluctant as I am to “name and shame” specific blog posts, this post published a few years ago at Kapost is a great example of content that could have been so much better but took the easy way out.

Firstly, it poses a question in the headline that it fails to answer, which often leads to disappointment (see above). Obviously the writer couldn’t possibly tell you with any certainty whether your content is turning people off or not, which begs the question of why the writer would choose to use this technique in the first place. Full disclosure — I’ve done this plenty of times, so no judgment.

Secondly, it’s too short. I’m all for brevity in content where appropriate, but this post is just a little too threadbare on actual content. Essentially, it’s 500 words that boils down to “don’t be overly self-promotional.” The post offers nothing in the way of actionable tips on how to craft better posts, and does little more than reference a third-party white paper that probably contains much more useful information – which the writer chose not to link for whatever reason.

There’s nothing “wrong” with this post per se, it just isn’t necessary. There’s no actionable tips, no unique insight, and no reason at all to read it.

Try harder – your audience deserves better.

4. Spend More Time Creating Compelling Headlines

If you’re going to ape any of the elements of clickbait in your ads, emails, or content, make it your headlines.

There’s an adage known as Betteridge’s law of headlines, named after British tech journalist Ian Betteridge, that states that if a headline can be asked as a question, the answer is almost always “no.”

Put another way, asking questions in headlines is lazy at best, and purposefully misleading at worst – not to mention they’re often perceived much more negatively than “straight” headlines. However, one notable exception to this principle is when your content focuses on data.

Framing headlines as questions when referencing data can be much more effective than playing it straight. Let’s take two headlines from real blog posts, both of which were published by Moz. Both posts covered the same topic, and both contained hard data.

Regardless of your intent, headlines are arguably the single-most important element of any piece of content. Even the most useful, actionable guide or compelling blog post will bomb unless your headline is sufficiently captivating. If you want to drive the kind of traffic that BuzzFeed and Upworthy articles generate, you’ve got to put in as much work as they do when it comes to your headlines.

5. Don’t Give Everything Away in Your Headlines

Remember earlier when we established that headlines had to be just tempting enough to get readers to click, but not so specific that there’s no need for them to click? Well, this highlights the dangers of giving away too much in your headlines.

Ad headlines, blog post headlines, and email subject lines are all a balancing act. The trick is to give your audience just enough to entice them to click (and hopefully read), but hold enough back so that you don’t give everything away at the outset.

6. Pay Attention to Your Data – But Stop Focusing on Virality

Despite what media sales professionals would have you believe, it’s virtually impossible to “manufacture” virality. There are simply too many variables to consider, not least of which is the enormous gulf between consumer content such as that published by BuzzFeed, and the comparatively dreary world of B2B marketing.

The more focus you divert to “making” something go viral, the less attention you can pay to factors you can actually control, such as the quality of your content. However, that’s not to say you shouldn’t be paying close attention to the data at your disposal. Just because you can’t manufacture virality doesn’t mean you can’t discover what resonates with your audience and give them more of it.

When planning your editorial calendar, be sure to examine your analytics data. Which articles were the most popular? What elements do they share? Did they contain original data or research, or feature a strong, contrarian perspective on a contentious issue? Identifying these commonalities should be an ongoing project that enables you to focus on giving your audience what it wants.

Mind the (Curiosity) Gap

Well, I made it almost all the way through this post without making a crappy pun. Despite this glaring personal failure, hopefully this post has given you some things to think about for your next content meeting.

As with virtually everything in digital marketing, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to bridging the curiosity gap in your content, and what works like gangbusters for one publisher may not necessarily work for another.

What insights have you learned from your own content marketing efforts? Get at me in the comments below with your success and horror stories alike.